Service Level Agreements

Expectations are a tricky thing. Everyone’s got one, and they don’t always align with what other people think. This is especially true working on a help desk or providing customer support. A customer calls in expecting an answer or a resolution in a specific timeframe… and many times the agent answering the call or ticket is stuck having to reset that expectation.

Folks get expectations from a LOT of place - but there’s one that can help make everyone’s life a bit easier and set those expectations out of the gate - the Service Level Agreement, or SLA). An SLA is basically an agreement between the service provider and the customer on how long something will take or how something will be done.

Essentially it’s a promise by the customer to have a specific expectation and in return the provider will meet that pre-set expectation.

Having worked on a help desk and helped agents working on them I find them to be both really great and a bit not so great.

Why they’re great!

SLA’s are great because they set a clear expectation that everyone can see. Generally they’re posted on a website and shared with customer groups so everyone has visibility into what they are. Customers go into a call knowing what to expect in terms of service. and agents know how long they have to complete any given request.

Why they’re not so great…

SLA’s aren’t so great for much the same reasons. Customer can now see how long something should take, meaning they can end up watching the clock and getting more anxious as it gets close to ticking down. They can also cause stress for agents since watching multiple tickets near their SLA is a bit stressful.

Some Terms

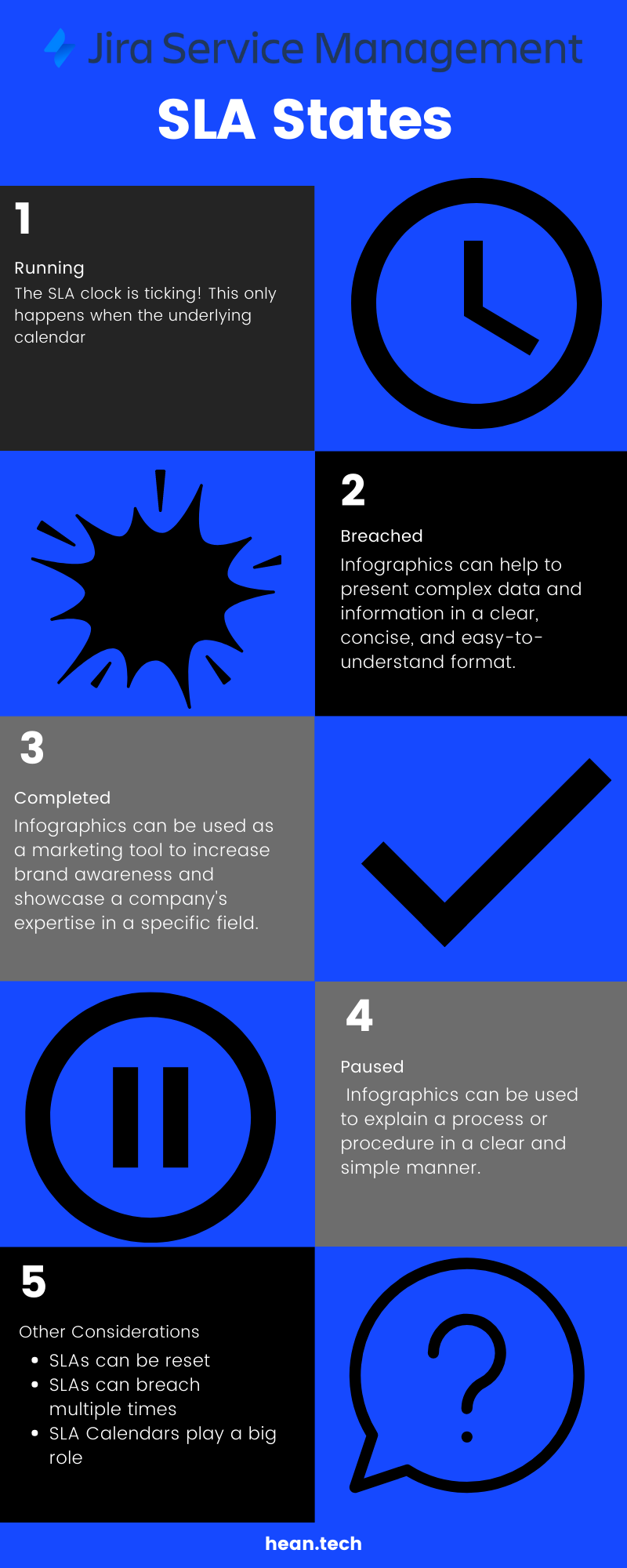

Breaching - When an SLA is exceeded. For example if you have 1 hour to do something and you take 2 hours, you’ve breached that SLA.

Paused - SLAs can be paused under certain conditions. This can be done when the agent is waiting for information from a customer or something is blocking the ticket. Generally this is utilized to ensure agents aren’t penalized for things they can’t control.

Active - SLA’s are active when their clock is ticket. Generally open tickets have an active SLA.

How to manage them

Folks who have SLAs setup should be on the lookout for the following:

Tickets nearing the SLA - Tickets within an hour or two of exceeding (breaching) their SLA should be closely monitored, and if needed additional resources should be added.

Tickets breaching SLA - These ticket should be examined to determine WHY the SLA was breached. This information is helpful to improve your processes and prevent it from happening again.

Tickets with a paused SLA - Tickets that have a paused SLA should be monitored to ensure they’re paused legitimately. It’s not uncommon for tickets to be paused and then forgotten about.

SLA’s in Jira Service Management

If you’re using Jira Service Management you can easily setup and track SLAs. Be default, you’ll have two

Time to first response (TTFR) - This begins ticking when a ticket is opened and stops once an agent responds. This helps ensure tickets get a quick response indicating they’ve been received.

Time to resolving (TTR) - Begins ticking when a ticket is opened and stops once a tickets is resolved. This is what most people think of when they think of SLA’s as it enforces a timeline to solve an issue.

You should consider when SLA’s are paused, commonly done when:

Tickets are waiting for customer - If a ticket is pending the customer to respond to take some action pausing the SLA lets the agent work on other issues.

Pending - If a ticket is stuck due to a third party it frequently pauses the SLA.

No Update Updates

Sometimes we don’t have anything to report on how things are going… this, however, is (oddly) important to report! Letting folks know you’re still on it is just as important as having progress for them.

Communicating with stakeholders is important (citation needed). These updates frequently take the form of status updates, alerts, progress reports and more. All of these things are very important to share and ensure everyone has. That said, sometimes there simply isn’t an update share… maybe nothing major happened, or maybe stakeholders already know what’s going on. The exact reason doesn’t matter… what does matter is sending an update.

Sending an update like this sounds weird since there may not be any change or anything to update people about. Sending an update feels a bit ingenuous, or like a waste of time. In scenarios where updates are regular and expected, continuing to send one is important since it keeps up the schedule. These updates let stakeholders know you’re still there and keeps them engaged. It gives them that regular touchpoint they’re used to and reassures them you still care.

The trick is what to put in this update… after all, there may not be a big change going live, or any fun metrics to share. Frequently I’ll simply say something like “No specific progress was made this week, but we’re still tracking towards our plan”. Updates like this let the stakeholders know we’re on track, and allows them to spend their mental energy elsewhere. It also takes the important step of letting them know you’re still aware of their request. After all, nothing is worse than a stakeholder wondering if you still care about the work.

This trick is very useful on bigger updates, but I also frequently use it on tickets…. Especially when nothing’s changed. I might be waiting for someone else to take some action (e.g. a third party vendor or teammate), or I may just not have been able to get around to working on that ticket. Regardless of the background, this strategy helps the reporter know you’re still there and can prevent nasty escalations. Instead of them complaining to your manager that you’re not paying attention, they know you’re on it, even if nothing is going on.

Order Pushing

Non-technical partners need to be careful to partner with their tech teams… many times they end up just sending orders to their technical partners. This not only results in a weaker relationship, but many times results in a weaker end product.

I picked up a great bit of advice from a recruiter - “Recruiters aren’t order takers, they’re partners”. The intention behind this is you shouldn’t go to a recruiter and say “find me a lawyer” then walk away. Instead, you should sit down with your recruiter and talk with them about what you need. What problems are you trying to solve? Why are those problems, well, problems?

This discussion helps the recruiter figure out what you REALLY need… not what you *think* you need. The difference between the two can be finding a great candidate, and not finding anyone. By partnering with the recruiter, instead of just putting in an order for something, you raise your chance of actually solving that challenge.

The same paradigm exists with technical teams (and I would imagine with ANY relationship). Many times we’re just told to install some system or make some modification by a partner team. The thinking is that the technical partner is there to take care of the technical stuff… which is obviously to install that new system. This approach, however, drives us nuts.

Instead of just telling, or even politely asking, your technical partner for XYZ solution, it’s a much better idea to start a discussion with them. Let them know more about what pain you’re experiencing, what solutions you’ve identified, and then ask what the best path forward is. At the very least this will build your relationship with your technical partner; they’ll see you more as an active partner in the relationship and less of a burden. At best, this will enable your technical partners to find better solutions… in many cases solutions you didn’t even knew existed.

Changing from order pushing to partnering can be challenging, but, like many things, it gets easier with practice. The next time you have something you need from your technical partner, schedule a quick meeting with them. Let them know you’ve got a challenge you need their help on and provide some background before the meeting. This will likely intrigue them, especially if they’re used to being order takers, and give them a chance to understand what you need.

Instead of approaching the meeting in a “Here’s what I need” mindset, approach it in a “I need your help on X” mindset. This will shift your perspective a bit, but more importantly it will show your technical partners you’re seriously about partnering. Instead of phrasing things as a definitive - “we need X solution by Y date”, phrase it as a question “So we’ve heard X solution would be a good idea, what do you think?”. This opens the door for your technical partners to provide their ideas.

Most importantly this approach will demonstrate that you value your technical partners’ experience in their area. This goes a LONG way to building a positive relationship that will pay off in the future.

On Proactivity

When we discover a problem or error the first thing we should do is let others know. This not only gets more eyes on the problem, but helps avoid others being surprised and escalating the problem.

IT does a ton of work to support a company. We make sure billing systems accurately charge clients. We make sure our HR systems pay everyone properly, and we make sure our websites are up and accurate. All of these things are incredibly complex challenges that require a great deal of expertise and skills to manage successfully. Despite of all this work, however, IT is generally perceived as a reactive function; we just sit around waiting until someone reports a problem to us.

Certainly some part of our function is reactive… we do, after all, have a help desk and support portal to solicit tickets. There will always be some portion of our work that is reactive, we cannot, after all, be everywhere at once. There will always be SOME challenge that pops up in an area we don’t have eyes on. Just because a small percentage of our work necessitates reactivity, we shouldn’t accept only being reactive.. Indeed, there is a LOT to gain from doing the opposite, from being proactive.

Being proactive means a number of different things in tech. Most importantly it means letting others know that something is going on. Being in IT means we get an advanced view of how the systems are operating. We get dashboards, alerts and reports that most folks don’t get… and even if they DID get them they wouldn’t necessarily understand what they mean. This makes proactive communication the single most important thing we can do to increase out impact.

I take this lesson to heart and make alerting folks one of the first things I do when I find a problem. (The only step I would take before this would be to stop the immediate bleeding to help minimize the impact of the problem). This have a number of advantages:

Get ahead of the problem - Letting folks know about a problem before they find it helps prevent the wave of “OMG XYZ thing broke, help!” emails/calls/slacks/visits/telepathic messages that will come once folks realize there’s a problem. Your email just saved god knows how many tickets.

Builds partnerships - This is an important one! By showing your partners that you’re actively watching out for them you build trust.

Rallies the troops - Proactive alerts also let’s your team know that somethings happening. This gets more eyes on the problem, and helps solve the challenge more quickly. It can also help tap into other teams sooner since they’re now aware of the issue.

The good news about being proactive is it doesn’t take much effort… a few sentences describing what you discovered and that you’re looking into it goes a LONG way to avoiding an escalation.

On trees

Keeping details in mind is incredibly important in life. Without them we can never really be sure what we’re doing… unfortunately many times though, we lose sight of this and suffer for it.

Details are important, it’s where the devil is (citation needed). Details are what allow a plan to come into focus and and idea to have impact. Without them we cannot fully shape what we’re working on, and can never really be sure we’re done with our task. Despite this, we frequently fail to fully understand the details on what we do. We embark on tasks without taking the time to fully examine the minutia that defines our work. Instead, we focus on the higher-level portions - concepts, ideas - that rely on the detailed work to really stand out.

On one hand I can completely understand the desire to avoid really getting into the details… it’s tedious. It can be boring. It takes time… and there’s SO much of it. Even what seems to be a “simple” project contains a ton of details when you zoom in. Asking questions like “who do we talk to about X”, or “what specific steps are needed to complete this task” makes those “simple” projects seem more complex… after all, we started with just installing a new piece of software, why does that have more than one step?

While it is true getting into details can make projects seem to stretch out, the time is more than worth it for a number of reasons.

Understanding the whole picture - Taking time to understand the details helps flesh out the entire picture you’re looking at. It’s similar to looking at a painting and noticing something new… suddenly you understand a new perspective on what the artist wanted to capture.

Avoiding pitfalls - Knowing the trap is there is the first step to avoid it, and investing energy in the detail work will help uncover potential problems that may have otherwise remain hidden. While identifying and planning for these challenges adds more time to your calendar, it will pay off by avoiding the need to fix those problems later.

Improving your skills - Getting into the details also helps you expand your skillset. You’ll find things you didn’t know were there, or connections suddenly become obvious. Like any skill, over time you’ll also get better at defining the detailed work, which will reduce the amount of time it takes to reap the benefits of this exercise.

On the other hand, however, I find it baffling when folks consciously avoid the details. I’m not suggesting that everyone involved in a project needs to be at the most granular level (indeed, executives need to exist at a high level and tend not to have time for detail work), but the project as a whole needs to be aware of details. Even something as simple and double checking settings on an email account should not be taken for granted (unless you want the whole company to see what’s in there…).

You can always take 15 minutes to kick around your projects details with your team. Ask them what’s missing from the plan, and then go find that devil.

Best intentions pave the road to massive headaches for other people

Some of the biggest headaches I’ve had to deal with were the result of really good intentions. As challenging as it is, remembering to treat these as learning opportunities (and not taking someone’s head off) helps not only fix the problem faster, but build better partners.

There’s almost nothing more dangerous than a well-intentioned individual who knows a little bit about how things work. This can be the combination of many factors, such as seeing a particular solution somewhere else in the past, thinking they know what they’re doing / thinking it “can’t be that hard”, rushing, and just good old fashion dumb luck. Unless other evidence exists I always treat these as honest mistakes.. That said, I’ve seen these crusaders end up:

Emailing a group of 1200+ people accidentally - Instead of just collecting emails it also forwarded them to EVERYONE on the alias…

Telling a VP a 60+ hour job should only take 2 hours - Nothing like being told to deploy something in 2 hours that you know from experience is over a week of work.

Crash a corporate network offline - Backing up a 60+gb harddisk over a cable modem is bad enough, but when it crashes an entire corporate network you know you’ve done REAL well.

(Fun fact - I was responsible for one of those….)

Personally I always encourage folks to learn more about tech and systems. This, in general, makes for more informed users and can make things easier overall. I’m constantly looking for ways to help people better engage with their tech, and to help foster that curiosity. I’ve also seen this approach ignite interest in folks who want to learn more about tech and systems, to the point of them changing their career and interests.

That said, a little bit of knowledge goes a long way towards wreaking havoc. Once folks get just a little wind behind their sails they tend to forget they don’t know everything about a setup. Many training videos, sessions and tutorials are tailored for a specific audience and use case… one your coworker(s) may be exceeding. The sense of confidence felt when making or requesting a change masks a lack of knowledge over what is really going on… which can result in massive headaches for tech teams when they have to clean things up.

I’m “Helping”

To help curb this… “helping”... I’ve adjusted my approach to working with non-tech folks (While tech teams certainly commit these errors I’ve recently found it to be much more common in tech-adjacent groups). In addition to giving them basic knowledge to do their job, I now also take the following steps:

Point out hidden dangers - Thinking through what MIGHT go wrong is a great way to uncover potential risks. I go through this before I setup training, and then use the output to better inform users. For example, if there’s a field I think they might want to use, but isn’t included in the training, I’ll specifically call it out and what it’s for. This helps avoid situations where they see it later and think “hey, that looks useful, let’s use that!”.

High Level Documentation - While I cannot expect my users to understand ALL the ins-and-outs of a system, I can expect them to know high-level basics. Knowing that Workday sends a termination file to XYZ teams is important info… and they should know that. Knowing reports are accurate as of last night at midnight is important info… and they should know that. I both call this out in training, and ensure there is documentation to back that up. Training also covers where the documentation is, and how to find it… while this doesn’t guarantee we’ll avoid those challenges at least I know I’ve given it to them.

Encourage them to come up with ideas… then talk to you - I have always encouraged my users to think up better ways to do stuff… now I’ve added a second step - talk to me (or someone!) about that idea BEFORE doing it. I frame it along the lines of “You’re a super smart person, so help me find better ways to do things. We need to keep in mind that there’s a LOT of other moving parts, so when you’ve come up with a new idea, let’s brainstorm on how to make it happen”. This both stops them from acting blindly, and also helps build better partnerships and trust.

Whoopsie

Throughout all of this it is important to remember everyone makes mistakes. I’ve watched experienced and trained engineers forget to deploy a change to production due to a poor file name. I’ve personally deleted over 5,000 trouble tickets by changing a configuration file (thankfully we could roll it back!). The important thing is learn and not do it again. This requires a great amount of support from your team, as well a company culture of safety and acceptance. This story of a man who lost $2 million is the perfect example - his company treats these as development experiences, opportunities to get better.

It can be incredibly challenging to not react poorly when uncovering these errors. (Why the *()@#$*&^ did you do that??!??!), and it is certainly a learned skill in responding appropriately. I’ve started taking specific steps to help both keep myself in check, but also limit damage and maximize learning:

Breathe - The damage has likely already been done, so taking a moment to breathe and assess won’t hurt much.

Quick Assessment - Determine a preliminary root cause and prevent further damage. This might mean rolling back some code, (un)plugging some hardware or making a quick phone call.

Alert Partners - Generally happens the same time as #2, but let any downstream partner teams know of the error. THis will allow them to help out with damage control and minimize surprises.

Deep Assessment - Dig into what happened and why. Understand as deeply as possible how the change negatively impacted things and what should have been done differently to prevent that from happening.

Deploy Adjusted Fix - Based on the assessment deploy the updated changes.

Share - Clearly document and share out a detailed assessment of what happened and how it will be prevented next time.

The individual who caused the ruckus should be involved in every step of undoing it. This will help build their confidence by improving their skill sets and give others more confidence in their ability going forward. The final step, “Share” is also critically important (and frequently missed) to ensure this doesn’t happen again. Saving this knowledge also helps ensure that other team members do not commit the same error (something that is sadly too common).

Data Analysts - Know Thy System

Understanding both how a system creates/stores data and how it is used is critical to being a good data analyst. Knowing these things makes it easier to interpret information and to tell a good story about any potential results. Failing to Know Thy System at best results in wasted in… and catastrophic decisions at worst.

“Know Thyself” is certainly an important concept to being a human. “Know Thy System” is an equally important concept to being a data analyst.

In addition to knowing data analytics concepts (not making misleading graphics, for example), a good data analyst also understands how data moves through the system(s) they analyze. This knowledge goes beyond basics and extends into how specific metrics are collected, how users behave and how data is stored. This background knowledge not only makes it easier for them to find the numbers they need, it allows them to draw better conclusions on that data.

Some examples I’ve run into include:

Knowing when tickets are assigned - Many reports on ticketing systems relate to who’s been working on tickets. Knowing when/how users are assigned tickets will impact the report. For example, if someone triages a ticket THEN assigns it, we can expect tickets to remain unassigned throughout the triage process.

When data is added to something - Some data fields are populated when a record is created (Employee ID, for example). Other data, however, may remain defaulted or even null. These defaulted values will appear in reporting, and may throw off results.

Where data comes from - End-user reports sometimes contain data from multiple sources/systems/etc. While this makes for easier story telling it can make troubleshooting or updating things more complicated. Being aware of how your reporting system pulls information reduces time to update things and makes it easier to explain how things were determined.

The problem with NOT knowing thy system

Understanding the UI and the users perspective isn’t enough to really know how the system operates. Many systems, for example, combine multiple metrics when displaying values such as Service Level Agreements (SLA), total compensation and others. Looking at the back end database tables can be incredibly confusing if you don’t realize that “SLA” really feeds 5 different dimensions.

As data analysts it is our job to know about these concepts. Failing to understand them will, at best, result in a LOT of wasted time as we dig through tables or configuration settings, and at worst, result in bad decisions being made about the data. Something as simple as not realizing your underlying data doesn’t include any data from January can be catastrophic; your customers will make business decisions on the lack of results from January… which aren’t real.

Helping others to Know Thy System

I’ve run into MANY situations where someone doesn’t have any background on the underlying systems and tries to make determinations on something. At best, this results in confusion as folks come to you, the Data Analyst with more questions. At worst, this results in conclusions being drawn from information that folks don’t truly understand.

In many cases we cannot expect our customers (folks reading our reports) to fully understand all the underlying concepts. This isn’t to say there shouldn’t be SOME expectation that they understand things, just that we cannot expect them to know anything close to what we do. To help bridge that gap, I’ve been following a few guidelines:

Always put comments in reports - Many reporting systems have a comment or text field. I’ve started always putting notes in there that relate to that specific report. These include a brief description of what the report is intended to show, and any call outs to specifics that may not be 100% obvious (e.g. a specific field showing a null/none until a specific time period, etc).

Proper Naming - Definitely another easy win - just name things more accurately. I try to keep a specific convention that briefly describes the report. This both makes it easier for me to organize, but also helps my customers find the right report more quickly.

Basic Documentation - In addition to cranking out reports and dashboards, I’ve found providing basic documentation on where data comes from is incredibly helpful. This doesn’t have to be (nor should it be!) a full data dictionary. This wouldn’t only drown your customer in too much info. Rather it’s a quick guide on what common metrics mean and how they’re pulled. Think of this as proactive defense against common questions.

Defects - What to do with them

While collecting defects is a great first step, there’s a lot more that can be done, including retroactive investigations and proactive avoidance.

Having determined our goal of zero defects, and determined what a defect is, the $10,000 question is what do you do with them. After all, it’s one thing to identify what a problem is, it’s entirely another thing to solve for it.

The easiest approach

Every company will accumulate defects as time goes on (or at least I hope they do… if you know someone who’s proactively solved every possible problem please let me know!). The type and quantity will differ, and may change over time, but at the end of the day there’s always a pile of things that need solving. The important thing is what is done with those defects.

The simplest approach is to collect them, which at its most minimal approach tends to be some kind of shared email inbox. This is a very common approach for smaller groups, or groups bootstrapping the process with no previous experience or resources. After all, it’s really easy to spin up a new email inbox and share out the alias with everyone.

This approach, however, gets out of hand incredibly quickly. The inbox will either get flooded by all the incoming requests, or trying to keep track of everything becomes incredibly complicated and convoluted. Having more than one agent (someone who responds to the emails) makes this even more challenging to keep track of (imagine 10 people monitoring a single inbox that gets 100’s of emails per day… how do you control who gets which email? How about metrics tracking? Followups?).

The next step

Another more advanced, but still very common approach is to collect these requests in some form of a ticketing system. Having a ticketing system adds some level of complexity to the process (it needs to be setup, administered, paid for, etc.), but this complexity provides a better foundation to provide support to customers. Equally importantly it provides a framework to draw data and insights from (e.g. when tickets were created, who made them, what they’re about, etc). These data dimensions make the more advanced work much easier.

Requests can come into the system directly, or be piped in from an email alias, but regardless of entry point those requests are monitored by a support team. This team is (hopefully) focused entirely on answering those requests. While it is possible to have part-time teams, breaking their focus onto other responsibilities will reduce both the number of requests responded to, and the quality of those responses. You are also preventing yourself from learning more about patterns in your requests since any given agent won’t have complete exposure to everything. It is also incredibly important to support these agents with whatever training or knowledge base information is necessary to handle the majority of those challenges. This is an ongoing goal, but something that must be started sooner rather than later.

A shared inbox or ticketing system is a necessary step, but it doesn’t do much, if anything, to prevent the defects from occurring in the first place (our actual goal). While the challenges/pain the defects cause must be addressed, simply collecting them doesn’t help stop the next defect from occurring.

Reactive analysis

To actually help reduce the number of defects, someone (or a team of someones) is needed to and analyze the incoming defects. Their goal is to better understand the defects that come in, and look for ways to help plug the leaks. What this team can learn from the defects is largely dependent on the quality of the incoming defects. This is partially reliant on the collection method (e.g. email vs. a sophisticated ticketing solution), but is also impacted by the teams ability to understand what the defects are and routing them appropriately.

By critically examining known defects, this team can then make recommendations to the business on how to prevent future defects. These recommendations may be the result of identifying patterns in defects (e.g. every tuesday we get a lot of tickets about entering time), or observations about improvements (e.g. update a button placement so users see it more easily). Since every business and group is different, the recommendations will vary, but the end goal is to provide guidance on how to stop the defects from recurring. This team should be formally and informally connected to the business units they advise.

Proactive avoidance

Reactively examining defects can provide guidance for changes to stop future defects, it would be much better to prevent those defects from ever occurring. To me, this goes beyond standard QA since some things cannot be easily QAed (for instance an onboarding program or policy). This is where proactive assessments come in. Think of these as pen-tests for other areas of the business; a complex examination of existing systems or processes that attempts to uncover faults before your customers (or fellow employees) find them for you.

This is further complicated since the business is constantly changing. It requires the totality of the process being examined any time a change is made to a process, a new policy is rolled out, or a new patch is released. This is no small ask, and requires a team that is equipped to go in and try to break everything in any way they can imagine. Say a payroll system is updated to provide more employee self-service (a recommendation from your defect analysis team). Your proactive team would need to think through a number of things, including:

What readily available documentation is available to employees?

Can it be easily found?

Are managers aware of the change?

What formal communications are going out to employees to let them know?

What information is made available during onboarding and retraining?

What other information sources should be updated (bulletin boards, etc)?

What downstream systems might be impacted? (change management)

The specific questions would differ depending on the changes and environment. This team may also opt to only focus on specific areas (e.g. payroll related items) to provide a more focused impact in higher-risk areas.

At the end of it all, it’s not a question of will there be defects, just when they will occur and where. While handling defects after they occur is necessary, groups need to better understand the weaknesses of their current processes and proactively plug them up. While it does take energy and time, it results in significantly happier customers.

Zero Defects - What is it?

Despite our best efforts every process or system produces some unwanted or unexpected behavior - defects. Many times our customers are the ones letting us know about them, which is less than good.

Somewhere along the line I picked up the idea that any problem (a ticket in my world) represents a failure somewhere in the overall process. This isn’t intended to point blame, or make us think like we’re failing horrifically when we gaze upon or vast collection of tickets, but rather to help us frame every one as an opportunity to improve. This failure could be in training employees, training managers, a technical glitch, or how an interaction with HR is handled. Regardless of WHY it occurred, it is still a defect that needs to be examined, understood, and never repeated.

What is a defect?

In general, however, a defect is any adverse or unintended behavior in a system or process. This may be further refined based on who you’re talking to and/or what industry your in. For example it could be the QA team finding a flaw before the production run in completed, or could be a piece of code that generates an incorrect result. “Zero defect” also implies that the defect is reported, that someone out there in the “wild” (not your team or testing) has found the flaw and is bringing it to your attention. This could be represented by a help desk ticket (common), and email (also common), a sticky note on your desk (less common) or a brick through your window with a note tied to it (hopefully least common). Regardless of how the message is sent, you are now in possession of a bright, shiny new defect.

In my world a defect is anything that results in the customer (fellow employees) having to reach out to a support team for help (this includes the HR, tech and IT teams). This outreach could be a complaint about someone’s behavior, confusion over a policy, or help finding a payslip. Note that this does not include any time someone has figured out something on their own (e.g. restarting their computer fixed the problem), or being able to look it up somewhere (e.g. HR policy information). The focus is on the group of individuals who have some problem and then have to reach out to one of our support teams for help. This makes things a bit challenging to totally control since it’s entirely possible an employee reaches out to a co-worker, manager, etc. and gets an answer without needing to reach out to support. Personally I’m not sure if this is truly a defect since they were able to figure it out without reaching out, but it’s a bit of a grey area for me. Regardless, there’s no easy way to measure those, so I stick with whatever happens to get into our ticketing system.

Rating Defects

Ideally 100% of defects are examined, understood, and never happen again. Unfortunately we don’t live in this version of reality, so some yardstick is needed to understand and rank them. It’s important for the teams that look at defects to sit down and determine what dimensions they want to use to sort these (such as impact to the bottom line, type of system impacted etc.) and then to share those definitions with stakeholders to help improve trust and transparency. When in doubt I tend to start with two simple dimensions, complexity and urgency since they are relatively easy to understand and allow for quick sorting of defects.

Defects range from the simple (where do I find my payslip) to insanely complex or in-depth (employees in a specific area cannot not log into to one part of a certain system) An important note that “simple” does not mean it isn’t important to whomever raises it. “Simple” instead refers to the likely response/solution (e.g. “Click this link to access our payroll system”). Defects are never “simple” from the “Well, your thing doesn’t really matter” perspective (especially when related to HR issues), and always have a real-world consequence to someone. This is part of an overall tech mindset that’s a bit beyond this post, but definitely something I’ll dig into later.

In addition to falling somewhere on a complexity scale, they also fall into an urgency scale. This scale can range from “I need my medical insurance confirmed so I can get my cancer drugs” to “Just wondering what our policy on XYZ is” for HR matters to “Our payment processing system is offline and we’re losing millions every minute” to “the icon on some little-used internal page is broken”. Similarly to how “simple” doesn’t mean it’s not important to the reporter, the seemingly non-urgent items are still important. The icon on that site is the Priority Zero for someone and should not be dismissed simply because it’s “not urgent to me”.

Having these dimensions on defects help make it easier to prioritize both how they are resolved and how they are investigated. An ultra-critical, ultra-complex item will likely be immediately addressed, but an in depth investigation will take time, while a low-criticality, highly complex item will likely wait to be addressed. Exactly what dimensions are used to sort tickets can be up to any given team, but SOME yardstick should be used to help the followup work on determining how to avoid the defect in the future. All that said, regardless of the metrics being used, it is still a defect, which represents a failure.

Next up are responses to defects, something I’ll take a look at a bit down the line.

When should Tech be involved?

Frequently technical resources are pull into projects at the last minute. This deprives the project team of a valuable viewpoint and raises blood pressure all around. Tech should be included as early as possible to best leverage their skills and avoid last minute scrambles.

Very commonly companies have to make important decision about what they should do. These decisions typically involve a number of different departments (legal, HR, finance etc), all of which provide an important and necessarily piece of input to the Decision. For some reason Tech seems to be frequently forgotten about during this step in planning.

Failing to plan….

Due to the expanding info-tech nature of work it is critical that technical considerations are taken into account during planning. This includes things like giving tech a seat at the table, including team members in planning meetings, and ensuring they’re included in updates. You wouldn’t, for example, not include Legal in a big decision, why is IT any different?

Planning is a very important thing (citation needed). Even the smaller projects or initiatives need time to be shaken out. Schedules need to be determined, resources need to be found (or borrowed… or stolen…) and communications need to be setup. There are a ton of moving parts that need to be managed, such as figuring out what teams are involved, and who is responsible for what. Many projects share some amount of requirements, for example having a unique email, that tend to be better understood by the project teams. Almost every project, however, can benefit from additional technical expertise, and this is where a breakdown frequently occurs.

While many pieces can be managed without technical support, almost every aspect can benefit from a technical view point. This may involve tools that the project team is unaware of, help developing an ideal process, or access to key systems. All of these decisions also will require some about of IT help, even if it’s just setting up an email alias or standing up a file share. Generally not having the tech teams involved early will result in either a mad dash at the end to get them up to speed, or a diminished project result.

“Just IT”

This boils down to mis/pre-conceptions about IT itself. After all, IT just pushes a button and the thing works. It can’t be THAT hard to setup a new email alias, so why include them at the kickoff meeting? This is only compounded as projects become more complex. (If you don’t understand the underlying concepts moving 2,000 workers around your HRIS seems like an easy thing, just a button, right?) . This apparent lack of appreciation for the complexities of modern information systems results in IT being left out of the loop. Several times I have been looped into projects with only a few days before go-live and asked to complete what should be 3 weeks of work in 3 days.

Including tech at the start of the project helps avoid these types of situations. On the one extreme is tech saying they’re not needed, but on the other is avoiding a massive complication. This may also require some amount of discretion depending on the topic (e.g. a super-secret merger or HR event may require more selectiveness), however, tech teams are used to handling highly sensitive data so it’s just another project to them. At the start finding the right person(s) on the technical side may be a bit of a challenge as the help desk expert may not know anything about the HRIS side of the house (and vice versa). One way around this is to include one individual from each tech team at least is consulted and asked if they might be needed. Another method would be to approach your tech leadership and ask them who the best individuals to include are since they’ll have a good idea of who’s best suited for the task.

Business + tech = win

Once tech is regularly involved you’ve given yourself a number of advantages. The least of which is IT becoming aware that something is going on. This doesn’t seem like much, but is a huge step in the right direction. Like any team they have restricted resources, so we’ve now given them a chance to put your ask into their planning cycle. This helps eliminate the possibility of not having the right resources available to do The Thing (or giving folks premature grey hair…).

Even better, it also allows IT to point out potential problems with your approach. While I have great faith in my business partners, tech is not their area of focus. Frequently this results in them sticking to habits / easily available things (google sheets, anyone?), resulting in tunnel vision. Maybe there’s an easier way to communicate with everyone, or maybe you’ve forgotten about some restriction. More diverse brains, earlier in the process, can only help.

If a technical resource cannot be included (maybe you don’t have one yet, or maybe they’re slammed), another approach is to find someone on your team who is more technically minded. Maybe this individual has worked in tech before, or works closely with the tech teams currently. While this person may not be a technical expert they should be able to at least point out areas where tech should be involved. The goal is to find a way to get a technical viewpoint on your project as early as possible.

All together now

Many, if not all, parts of a businesses project can benefit from including technical resources as early as possible in the process. At the very least you’ll avoid last minute scrambles, but more likely you’ll enhance the overall project in ways that are hard to see at the start. You’ll also build a better relationship with those teams, improving overall operations and helping improve future projects. Your tech teams will thank you as well, since they’ll feel like they’re part of the great team instead of being delegated to being “just IT”.

Remember : There's a person behind that ticket....

It can be REALLY hard to remember that there’s another live human behind the ticket you’re working on. Take the time to connect with them on a human level, not only will the ticket go more easily, but you’ll forge a great connection.

There’s a fascinating thing that frequently happens when someone puts in a help desk ticket. They stop being a person and start being just… a ticket.

While this is useful for doing things like tracking trends, or analyzing problems, it presents challenges on how the problem is solved. Abstracting the person from the problem sets ourselves up for situations where our agents treat the ticket as just that - a problem - and not something that impacts the life if another person.

The usefulness of tickets

While smaller offices or organizations can rely on the “Walk up to XYZ person and get help approach”, this quickly breaks down at scale. First, after some point not everyone knows the right person to go. This makes it a frustrating experience to find help since you first have to go through a treasure hunt. Second it’s really hard for organizations to have enough of the right person at the right place at the right time to really matter (how many IT help desk techs is the right number? What if the location only has 2 employees, should they have a third employee who just does IT work?).

Since it’s (unfortunately) not possible to scale 1:1 human connections with organizations, we have to rely on some type of system to help us. This system should allow us to track multiple requests at a time, provide specific (hopefully accurate) responses, and interact with our customers. Frequently the thing that does this is a ticket. This makes tickets incredibly useful things, as they allow us to track, codify and organize pieces of work that have to be completed.

Given the size of some environments this is especially important as thousands, if not hundreds of thousands (or more!) issues pop up every year. While some percentage of the population will figure out a way to get face-to-face service, the vast majority of folks will interact solely with whatever ticketing system is in place. While this certainly makes it easier for the group providing support (IT, HR, whatever), it results in some interesting behaviors that may not have cropped up if a 1:1 in-person interaction were taking placee instead.

Do you have a ticket?

Many times the first questions out of a support techs mouth when presented with a customer with a challenge is something along the lines of “Ticket number”. Hopefully it’s more polite than that, so let’s go with “Could you please let me know your ticket number?” as the default. Already we have a problem. Instead of acknowledging the person in front of them (and almost as important acknowledging the pain that person is experiencing) the tech has gone straight to the ticket. While this may be a result of some process the tech is trained on, it immediately divorces the person from the equation.

While this makes complete sense (I certainly agree work needs to be accounted for), it immediately pushes the conversation away from help a person and towards placating a system. Systems are intended to serve us, to make our lives easier, not to enslave us to process and procedure.

To help combat this I work on starting those conversations with something like “What may I assist you with?”. I make a conscious effort to use “assist” and not “help” since they help frame the conversation. “Assisting” someone makes it a more collaborative, “us vs. the problem” approach, while “help” makes it more of a “you clearly can’t do this yourself, give it to me”. While this difference may seem minor, it makes the customer feel like they are part of the solution, instead of part of the problem. This becomes important when I need them to do something for me (reboot their machine, send a screenshot etc.), or if the problem comes up again (they’re less likely to think I”m incapable and more likely to want o work on a solution).

PATS (Person Abstraction Ticketing Syndrome)

It’s a little easier to avoid this abstraction with in-person (even video) requests since you get immediate body-language feedback and can more easily build a connection with the customer. Things can get really hairy when interactions are solely through a ticket and there is no direct connection with the customer. In these instances both the agent and the customer can forget they are working with another live, breathing human. At best this shows up as a different tone in responses, at worst customers get shuffled around between different teams until they get fed up and escalate.

This breakdown occurs since tickets cannot capture enough information (let alone the information provided by body-language or spoken word). Frequently they don’t even come close to soliciting questions that pull out context, for example not asking WHY something is being requested. This relatively lack of information makes it very easy for the agent to treat the ticket as another piece of the computer - something to be dealt with using as little energy as possible.

The customer, unfortunately, is in the same boat as the agent; they’re not getting enough information either. Compounding this is the frustration they feel due to the underlying cause (e.g. their computers broken), and the frustration of having to navigate some ticketing system (No one’s ever told me it’s a joy to use a ticketing system). Now, on top of that frustration, they have received what is likely a curt response (or at worst something totally unrelated to their request) to their plea for help.

As work on the ticket continues this transforms into a nasty reinforcing loop. The agent becomes more and more annoyed at having to deal with that particular ticket, and the customer feels more and more frustrated at not getting what they need. This tends to result in agents resenting customers, and customers thinking agents are un-caring machines. Eventually one of a few things happens:

Miraculously the ticket gets resolved - both parties are relieved, but not happy

The ticket gets transferred - The agent realizes they cannot help the customer so they punt them to another team. This effectively restarts the process, but does nothing to reduce the customers frustration.

The customer gets fed up and escalates - This can take the form of an email to a manager/director/C-suite and is not a lot of fun.

Even the best-case scenario is not a good once as the steps taken to get there were painful for both sides. In order to avoid these less-than-ideal outcomes, we may need to take a few drastic steps…. Remember they’re human too, and Get out of the ticket.

Remember they’re human too

This is something I always (try to) keep in the back of my mind when I work on tickets. Whoever is on the other end of that digital paperwork is another living, breathing person who needs me to help them out. Depending on the day and the person this can be more or less challenging, but the ideal end result is to treat the ticket like I would someone in real life. I wouldn’t for example, not respond for 3 days to someone who is standing in front of me saying “hello” (hopefully they wouldn’t stand there that long!). Nor would I respond to a detailed plea for help by running away and telling someone else to deal with it (e.g. blindly reassigning the ticket).

While it’s true the rules and expectations for dealing with tickets may differ then those for in-person interactions, we still need to push ourselves to treat customers the same. Remembering that they are, in fact, human, and do, in fact, need our help, is a quick mental shortcut to improving their interaction. Very frequently this also helps improve the relationship with your customer - they feel like they’re being treated well, so they will be easier to work with. This helps solve challenges on both sides, the agent feeling like something’s being dumped on them without enough info, and the customer who’s feeling like they’re being treated like a machine.

Getting out of the ticket

There are tickets that, for whatever reason, blow up and escalate. Maybe it took too long to resolve, maybe the customer doesn’t feel like you’re responding fast enough, or maybe the customer cannot effectively describe their challenge in the ticket. The reason doesn’t matter, but this is the point in time where the agent has to get out of the ticket and setup some in-person connection (not that they could’t do this earlier, they should!, but they REALLY need to do it during an escalation). This could be walking to the customers desk, video chat, phone call etc. but the point is to make a more human (and real-time) connection.

Doing this solves a number of challenges. First it demonstrates the agents sincerity in resolving the issue. This alone can have a huge impact on the situation (especially if the ticket has been sitting, or going back and forth for a while). Second it removes the distance a ticket creates and allows for more immediate feedback. Now the agent doesn’t have to wait for a screenshot, they can see exactly what’s happening. Third it helps build a real connection between the agent and the customer. This is incredibly important to both the current challenge, but more importantly it builds a relationships between both sides.

This third benefit is the most important since it builds towards the future. Next time there’s a ticket the customer is more likely to provide more info and be a bit more understanding in delays. The agent is more likely to give the customer the benefit of the doubt and provide better support. Additionally both sides will tell other people about the interaction. The customer will impact how others perceive their help desk and vice-versa. This ripple effect is immensely powerful and helps stop the negative feedback that crops up with ticketing systems, and (even better) helps improve the relationship between tech and partner teams.

Only Human

At the end of the day we’re all human. We do the best we can and sometimes we make mistakes. Regardless of the situation we still need to treat each other as living, breathing entities and not as lines of text on a screen. Keeping this in mind helps elevate both the level of service provided, but also the relationship between agent and customer. The strength of this relationship is directly related to how our customer perceives us, impacting how they treat us and what they tell others about us.

Keeping the human aspect at the core of support not only helps the customer feel heard and respected, but improves our workplace and job satisfaction as well. After all, who wants to work at a place that treats its people like machines?

On Entering Tickets

We’ve all had to put a ticket into something SOMEWHERE. Despite our collective practice, many tickets do not provide enough info for folks to get the help they need. Here are some tips.

Ticketing systems are everywhere, airlines, apartments, work. Everyone's reached out to one (sometimes not knowing it's a ticketing system!) at some time before, but despite the ubiquity of them many of us aren't the best at putting in good tickets.

Good tickets contain enough info for the person at the other end to understand what the problem is and determine a course of action. These tickets tend to include things like screenshots, error codes and descriptions of what was going on at the time. They not only provide the WHAT, but also the HOW and the WHY behind the ticket.

The bad

Before we look at what makes a good ticket, we need to understand what makes a less than good ticket. Consider the following (let's also assume the ticketing system knows who you are, what time it is, etc):

“Help! I can’t log into system ABC.”

This does tell us some information, that you cannot log into ABC, but the information provided is very limited. If I'm a very good tech I would first check to see if you have access to ABC, or if you're even supposed to be able to (its surprising how many times people try to log into systems they shouldn’t!). More likely, a tech will look at this, roll their eyes, and respond with something like:

“Ok, tell me what happens when you try to log in.”

While this response is typical, it doesn’t do much to get more information from the customer, and it doesn’t help establish positive rapport (not the scope of this discussion, but also very important!). Ideally the tech should do something more like :

“I understand you’re having trouble with ABC. I see you do have an active account in ABC. Could you please got to this link, try to log in with you username and password and send me a screenshot of your entire screen with what happens?”

I won't get too deep into how to properly answer tickets (a fascinating topic worthy of it's own discussion!), but this approach provides clear next steps for the customer. It also clarifies some assumptions, such as the user knowing where or how to log in, or them forgetting their credentials.

A Good Ticket

Short of just getting “Help!” (which does happen!) the example above is basically a worst case. A good ticket is one step up by providing more specifics, such as an error or screenshots. Thankfully more often than not customers fall into this bucket, mostly due to previous experience and/or training. It looks something like:

“When I try to log into ABC I get a ‘account not found’ error, help.”

This clearly states the problem, and provides some technical info to look into. It's better than the bad example since we get that error message, but even here more info would be really useful. For example a link to where they logged in, or telling us it worked yesterday.

Really Good Ticket

Rarely, oh so rarely, I see an exemplar. A ticket worthy of being printed off, framed, and hung on the wall as a shining beacon to direct people to. Something like :

“I tried logging into ABC at this link, but got a ‘account not found’ error (see attached). I could log in with my username last week, and don’t think anything’s changed. I need to get in to pay everyone. Help.”

This one gives us everything:

What - they can't get in, and am error plus screenshot

How - at a specific website, with info on it working before

Why - a business reason which helps determine priority

This information removes a lot of the guesswork for the tech. They should still double check, but now they know what to look for, and when to look (sometime in the past week). It’s also possible this info will trigger an immediate answer (e.g. system maintenance is ongoing and locking folks out), or otherwise clue-in the technician to something that may be impacting them.

While I concede our users won't do this all the time, we need to set the expectation on them to give us good tickets. Folks should be regularly reminded how to put in tickets, and that putting them in properly is beneficial for everyone. Not only does it make our techs lives easier, it decreases back and forth, shortens response time and makes everyone happier.

Ticketing system basics

Ticketing systems help us keep track of our work, and many have lots of bells and whistles. At it’s core, however, there’s only a few things that are REALLY needed.

Tech teams of all stripes rely on tickets to track their work. Tickets may be put in to ask for updates ask for new work or report problems. They may be put into a formalized ticketing system like JIRA, recorded in email (please God, don't do this!), or even written on a board (seriously there's free tools to help!). Regardless of method of collection, system used or content, what a ticket contains is incredibly important to it being treated properly.

Bare bones

At the very least tickets need to contain some basic information. This includes things like:

Reporter - the individual who provided the ticket is critical in providing additional info, clarifying questions and confirming it has been completed. Many systems record this automatically. While possible, anonymous tickets should be avoided unless absolutely necessary and clearly justified (e.g. anonymous complaints)

Assignee - having a single (yes, SINGLE) owner of a ticket helps ensure clearer communication, accountability and follow up. While this person can change, tickets should always be clearly connected to someone. Depending on the type of ticket this might be a project, manager, development resource or help desk technician.

Description of request - this generally comes from the reporter and details what the ask is. Frequently this is lacking in information (I can't log in), requiring triage of some form to get more info (can't log into which thing? What did you try?). Because of this it is incredibly important for the reporter to be very clear and accurate in their request.

While there are certainly other data points that are useful (time entered, labels, tags, priority, etc) if you can nail those three things 100% of the time things should go (fairly) well. The more complex the system is the more fields you'll tend to see as well (e.g. which team owns this? Can it link to a knowledge base of some kind?).

Additionally useful fields

The above are critical and should be mandatory for everything, but there is a lot more interesting things to be learned. Once you've captured basic information it's very helpful to know more about that info (metadata). Some of my favorites include:

Time entered - this timestamps can be used for a lot, including stack ranking (oldest first), handling expectations (we only got your ticket last night, chill out) and developing SLAs (especially when combined with Time Closed).

Time closed - another timestamps telling you when the ticket was closed. Very useful for fending off repeat requests (we already answered this last week), building SLAs (every ticket solved in 24 hours) and determining Mean Handle Time (MHT).

Tags - Also known as Labels, these things allow you to sort tickets by them. Generally requires a human to attach (e.g. reports put a 'bug's tag on tickets about bugs), but allows you to slice metrics by them (e.g. what's your MHT for bugs vs questions).

Pandoras box

One of the downsides of collecting this data on your tickets is folks will begin expecting more from you. For example, expect to start reporting out on how many tickets come in, which areas report them, average response times, etc. You will also likely be held accountable to some agreement around resolution times or MHT.

While the 'downside' can be a bit annoying since you'll now need someone to actually gather the metrics and report, it gives you a lot of power. Once you get a baseline you'll be able to do some interesting things:

Targeted help - you might find certain groups or areas report a large number of problems. Once you know this, create specific training just for them to help reduce their numbers (make a game out of it).

Prioritization defense - once you know some tickets take more time than others, or have a bigger impact than others, you can more easily prioritize work. Even better, you can show your partners WHY you're doing that, which will reduce pressure on you to justify yourself.

Team support - frequently tech teams get overwhelmed or blindsided by waves of tickets. Knowing what tends to come in, and when, gives you the ability to plan ahead and get your team more training, or clear their calendar if needed.

Having this information is not nearly as important as having the discipline to actively manage it. Reports, after all, are useless if they're not maintained or read! Keeping only a few basic metrics, however, is easy enough to do (especially with today's tools), and provide a lot of advantages. Even if you've already got a solution in place, take some time to reevaluate it, you never know what improvements you can make or what you'll learn.

Afterthought of an afterthought

HRIS tends to be the forgotten cousin of IT - it’s frequently brought in at the last minute (if at all). Building better partnerships with HRIS helps both sides, as the business gets better results, and the tech team gets less grey hair.

Very frequently businesses need to make decisions about the business. These may be big or small decisions, but they all have one thing in common - tech/systems partners should be included in them sooner rather than later. This is doubly so for HR Information Systems (HRIS) since many highly sensitive things (like payroll) will be impacted, and very frequently the complexity of those systems isn’t fully appreciated by the business.

Oh, right.. we need that.

I frequently joke that IT is an afterthought. After all, no one starts a company to fix their own computers. Eventually, though, someone realizes that yes, you do need someone to manage your IT resources. Once this happens, things tend to get better for IT. The business fully (or at least mostly) realizes the need for IT resources, but this generally doesn’t flow over to HR. This results in HRIT becoming an afterthought of an afterthought - after all, we have HR Generalists / Coordinators / Business Partners to handle running HR, why do they need systems experts?

This is also compounded as HRIT and IT are only cost centers (would love to hear if anyone’s found a way to change that!). Since we don’t obviously increase profits it’s harder to justify why they exist. It’s also hard in some cases to prove their actions save money (how many dollars does a good knowledge base page save?). While it is possible to break down ticket cost etc. that also takes time and money, resulting in a nasty spiral of not wanting to do the work to prove it’s worthwhile since you don’t know it’s worthwhile.

Being a double afterthought results in problems ranging from processes being done manually that can/should be automated (manually emailing new hires vs. automating with free add-ons), to catastrophic problems resulting from the lack of understanding / planning (for example paying groups of terminated employees well after they’re gone). In my experience these problems are brought to the HRIS teams attention… but only AFTER the impact has been felt by the company.

The problem is this is the same as ignoring leaky pipes in a submarine, eventually the “savings” of not pumping up HRIS will result in a massive problem.

Leaky Pipes

Since HRIS is usually the last player to the party (or at least the last invited), we tend to only get looped in at the last possible second (“We need this live tomorrow” is a common request…). What kills me about this is many times I hear that planning for that initiative had been in the works for weeks, of not months, before hand. I very frequently find myself wondering how we can have so many smart and talented folks around, but constantly fail to include critical elements early enough in the process.

Some common things I hear about why HRIS isn’t included earlier, my thoughts, and possible solutions:

This project is highly confidential/legal/sensitive, so we have to limit the people involved

One of my favorite reasons (especially the confidential part). I completely understand the need to keep information contained, but every company I’ve ever worked with has had me sign some type of NDA. In addition, HRIS teams tend to deal with highly sensitive information as a matter of course (SSN, pay scales, home addresses, etc). It is expected that we are good data stewards, so your list of terminations is just like any other spreadsheet to us.

Solution - One of the simplest things to do is select one individual from the HRIS team (e.g. the manager) to get advanced warning that things are coming down the pike. They don’t have to get specific details, but a general outline of what is required is enough so they can think through possible fixes. Ideally this person understands both the system and the business ask well enough to make it generic so the team can plan.

We didn’t realize the impact on our systems

Any time I hear this one I scratch my head. I find it hard to believe that no one on the project team realized your plan to change compensation for 1,000 people wouldn’t, in some way, impact HRIS.

Solution - Involve your HRIS or IT teams in EVERY major change you consider. You wouldn’t leave Finance out of a discussion where you didn’t know with 100% certainty they’d be needed. At the very least include them in the “I” of your RACI charts (or whichever flavor your company prefers). This way your HRIT teams will at least be aware of whats going on and will speak up as needed.

We spoke to so-and-so and they didn’t think we needed to do anything

This generally results from someone on the project team (or their managers) making assumptions about how HRIS operates (similar to “This other place I worked at did it this way…”). The outcome tends to be dramatically skewed expectations from the project team that, at best, will alienate your HRIS teams (e.g. a change should . “only take two hours” but instead takes 4 days and 2 employees to fix).

Solution - This is all about proactive partnerships. Special project teams should regularly meet with HRIS teams to understand basics of the systems such as estimations on standard requests, downstream impacts, etc. Not only will this help alleviate #1 and #2, it will foster better collaboration and build trust.

Plugging the leaks

The best way to get over being an after thought is to build proactive relationships with HRIT and partner teams. This can take the form of a monthly lunch and learn where systems basics are shared, or specific meetings to go over features, or formalized partnerships where team members regularly sit down and go over challenges. At the very least this will help give partner teams a better understanding of just how complex the plumbing is.

I tend to prefer in-person sessions where I walk through specific processes, or demonstrate how specific features work. While I tend to have a plan in mind when we begin, the discussion frequently veers off into different areas based on comments or questions from my partners. Personally this is some of the most interesting discussions to be had about systems. Getting a systems expert and a business expert in the same room is bound to come up with some good topics.

To help avoid last-minute “gotchas” related to HRIS, we all need to remember that every aspect of what we do is complex; often more so than we think. Taking time to help the business understand our complexities, and appreciate the effort required to make “simple” changes, more than pays off. It not only helps strengthen relationships, but will pay dividends in future projects as partners are better equipped to help address challenges before they come up; hopefully bringing HRIS out from the shadows of being an afterthought.

On bringing solutions

I always appreciate when my partners think through challenges before coming to my team. It does get a bit dicey when they bring us solutions they think will be best…

One of the most common challenges I’ve run into is having a partner come to me with a solution to a problem they’ve run into. This might take the form of “Have Workday do XYZ”, or “Build me this type of report”, or “Use this tool to do X”. Part of me really appreciates my partners taking the time to figure out what they want to happen… but a much larger part of me has a blood pressure spike and a few more grey hairs pop up.

Why the grey hair?

I really do appreciate my partners taking a stab at figuring out what’s going on. I get the grey hair for a few reasons:

Generally partners don’t have the full picture - Partners usually are only aware of the aspects of systems they interact with (which is all we can expect or ask of them!). This means they frequently are unaware of other solutions, or of interactions with other systems.

Partners are usually not technical experts - Nor should they be! I frequently tell mine I’m not an HR expert and I’m glad they’re around to do that. That acknowledgment also means I don’t go tell them how to fix HR challenges though.

Their focus is only on their stuff - One of my favorite phrases is “This is my P0 (priority 0)”.(more on that in another post!). Everyone (me included!) has a personal list of what’s important, and nothing else comes close. This makes things problematic as partners get tunnel vision on just their own items.

When a partner brings me a solution they’re generally already stuck on one (or more!) of those items. This means I have to take time to talk them down (all that de-escalation training at the help desk REALLY comes in handy!) and explain why their solution may not be the best idea.

Why it’s challenging

While I find it great that my partners put thought into a solution before they come to me or my team, it tends to set us up for failure in a few ways:

They put energy into it - Once someone puts time/energy into something it’s MUCH harder to change their mind

They’re “stuck” on their idea - Everyone likes their own ideas, and it gets particularly challenging to try to change their thinking.

The clocks (usually) ticking - Since my partner’s already taken time to come up with an idea we now have less time to build one together. This can be particularly troublesome with highly sensitive asks.

These generally occur in some combination, which makes the initial talk mostly focused on talking my partner down or trying to find ways to reshape their thinking.

Just come back off the ledge…

This is where I find connections with my partners to be particularly important. When I first work with someone I don’t have any credibility (other than being the “IT” guy), so I have to build it on the fly. Once I have an established work relationship that process is a LOT quicker, allowing us to get to the source of the problem much more quickly.

I use a number of tools/tricks to help with this, but some of my favorite:

What are you trying to solve with this? - This question helps my partner focus on the problem and gives me an “in” to have them demonstrate it. This makes it easier to change their thinking about a solution.

Why do you want to do this? - Similar to the above it makes my partner explain how they got to their solution, which helps me figure out WHY they (think they) want it.

Who else have you spoke to about this? - This is a great question to help determine where their solution idea came from. This can then help me figure out how they came up with their idea.

Getting to a good endpoint

Usually this boils down to spending an hour with my partner to go backwards through their solution. This can be a painful process, but helps us uncover why they wanted that particular thing and, more importantly, better understand the underlying problem. There are some times when their solution ends up being the one we go with, but many times we land on a different approach (usually based on information my partner didn’t have, e.g. how a system operates).

The most important aspect of this approach is the time spent with my partner. This helps build a positive relationship with them, which will only help me out in the future. As the relationship progresses both my partners and I get better and presenting challenges, and developing solutions.

Trust. But Verify.

Trust what you’re seeing/being told…but always verify it with your own testing.

One of the favorite things I’ve learned working in IT is to “Trust. But Verify”. I find it especially helpful when I answer support tickets as users are frequently either mistaken about what they’re seeing (an ambiguous error message), or unable to provide all the information (e.g. they don’t realize they’re missing permissions). To me it means that I trust that the partner or customer I’m working with is giving me their best possible info, but that I still need to back it up and look into it myself. Pulling up the floorboards this way not only helps me determine the root cause of whatever’s happening, but also helps me learn about systems and processes in new ways.

Generally I don’t say “Trust, but verify” to the folks I’m working with (although I do use it in mentoring/coaching sessions to help folks get in the mindset of validating everything). Instead I have a number of variations I use, things like

“Prove it” - Generally more in teaching situations where someone tells me they have the answer / they’ve done something cool. I use this phrase to challenge the person I’m working with and see if they’ve really done what they think they’ve done. Also something I only really use with folks who know me and won’t be put off by the wording.

“Can you walk me through what’s happening?” - The more user-friendly version of “Prove it”. Everyone in IT know folks tend to report only small portions of what’s going on, this helps uncover the underlying pieces. It also helps my partners learn the process a bit better since they have to go through it a few times so I can understand it better.

In addition to answering support tickets, this phrase is also great when performing any kind of systems analysis. Frequently what I see isn’t what you get (the opposite of WYSIWYG). I’m finding this to be especially true as I navigate new systems (like Workday) that have underlying architecture or concepts I am unfamiliar with. Simply accepting what I see is a wonderful way to setup myself up for failure! In the same way I trust that my partners are telling me the best info they have, I have to trust that my current understanding is the best one I have at the time. I’m finding I cannot stop there though, I have to dig in deeper to verify what I think I see or know. This might take the form of reading up on documentation (everyone’s favorite past time!), or if I’m lucky asking a teammate who knows more than I do for help.

Every so often I give myself a reminder of this and forget to verify…. this usually results in a bit of rework as I have to go back in a fix things, but the silver lining is I both reinforce this lesson and learn the process a bit better. As a result I’ve found I constantly remind myself to not only trust my own work, but followup and verify that it’s the best I can do.